Ludum Dare 43 Post-Mortem

We made another game for the latest Ludum Dare game jam. It’s called QUELTRIS, and you can play it right here.

In this post I want to describe the game design process: how we came up with the idea, how the initial idea wasn’t fun at all, and how we turned that around to find something that was worth playing.

The idea

The theme this time was Sacrifices must be made. We started by brainstorming around that theme, trying to find an interesting setting and a gameplay idea that would fit. We took the theme rather literally and quickly gravitated around the idea of an Aztec god asking you to sacrifice pawns.

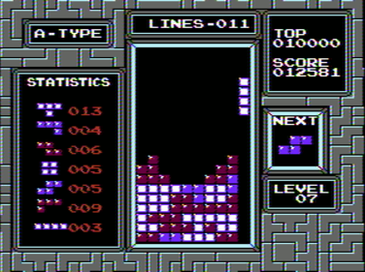

On the gameplay side, I suggested to do a match-3 (think Bejeweled). Partly because we had been playing PuyoPuyo vs. Tetris the night before, and partly because I thought it was an easier target for the allotted 72 hours. In Münster, not only the game was much shorter than envisioned, but the gameplay felt wonky due to falling short on time. For Bright Plateau we did manage to make a decent-sized game (for a Ludum Dare), but as I designed the levels the last day, we didn’t know how fun the game would end up being until a few hours before the deadline. This time, we focused on getting a good gameplay first.

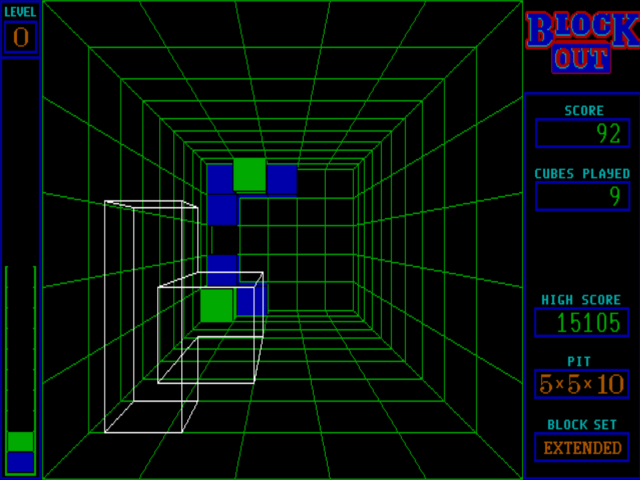

Of course, we didn’t want to just do a Bejeweled clone, so we sketched some ideas on how to iterate on the formula in an original way: maybe using a different swap mechanism? Or changing the grid? We looked at QbQbQb, a game where you put pieces around a planet, and at Block Out, a first-person Tetris that has you looking down the well in 3D as a tetromino.

Trying to sketch how a circle grid would work for us, Merwan had an idea: what if we had a round, bottomless well, and the player would sacrifice pieces by push them down the well? We both instantly loved that idea: it was a simple mechanism (push) that perfectly fitted the theme (sacrifice).

Now, at this point we didn’t know if the idea was enough. We had a good idea, but needed to see it in motion. I started making a playable prototype while Merwan began working on the visuals.

The prototype

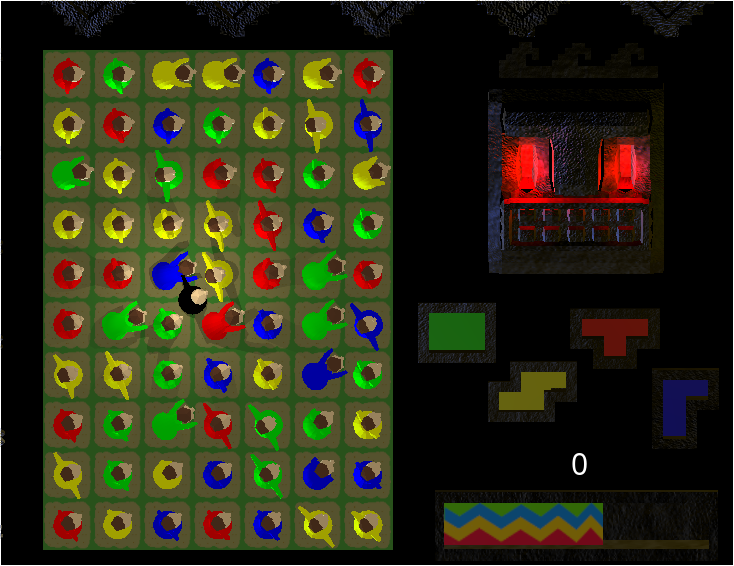

At 21:19 on the first day we had a playable prototype:

The player moves the white triangle at the top to switch columns, and can push the current column down in order to match three of more pieces of the same color. Every move consumes blood from the gauge, while making matches fills it back. When the gauge is empty, you lose.

The first thing to note is that it is nearly a complete game. In that sense, our focus on prototyping was a success. Adding a little polish here and there, and we could have submitted it! Needless to say, we felt pretty good about our progress.

Except for one thing: the game wasn’t fun. At all.

In the video above I’m just pressing buttons at random, without thinking about whether my move will make a match. I don’t need to: most moves will make a match. Since we are moving a whole column down, 7 pieces change position, making 7 places for a potential match. As I keep pressing the down button, I make many matches, just at random. The game does not challenge me, so I’m not engaging with the game. It’s just not fun.

The blood gauge was actually an addition I made after finding out that the push mechanism was simply not enough. Adding the gauge was supposed to force the player to consider each move, but as matches were easily made, the balance was still off.

We were in a crisis. We had a good idea, or a least we thought we did, but it wasn’t fun. How could we salvage it?

Finding the fun

We can feel when a game isn’t fun, but how do we add fun back in? How do we improve the mechanisms?

A first step is to understand why the game isn’t fun in the first place. Here, I feel the game is lacking meaningful choices. At any given time, the player has three moves at his disposal: move left, move right, and push the column down. Now, a low number of low-level moves isn’t necessarily a bad thing; some games manage with as many, or even fewer. What is more important is what decisions these moves enable. There are seven columns, and the player has to choose one column to push down in order to progress; that’s exactly seven choices at a given time. Seven is a low number of alternatives to weight, which might make the game trivial. But worse: actually weighing these alternatives is pointless, since matches come so easily. You can pick any column, push it down a few times without thinking about it, and you will probably make a match. If you don’t, just move to the next column. Even if you try to play thoughtfully, looking for matches is trivial. Since we have too few interesting decisions to make, the game ends up feeling boring.

Doubt cast over our enthusiasm. After grabbing a bite, we looked at how other games with similar mechanisms managed to be fun. Tetris mixes two levels of decisions: at the tactical level you have to move the falling pieces where they won’t create too many holes, and at the strategical level you have to think about leaving space for an eventual ‘I’ piece. PuyoPuyo has the same depth, but here the strategy is about scaffolding for combos long, juicy combos. In both these games, the player is constantly trying to clear the well while the game keeps throwing more stuff to handle, which creates a nice tension. In Bejeweled and Hexic the tension arises by creating matches while managing the random pieces coming from the top. Both also have strategic aspects: Bejeweled lets you setup combos for more points, and Hexic requires you to build “flowers” patterns in order to win.

Other games succeed at using match-3 mechanism on the tactical level, but mixing that with another genre altogether at the strategic level. In Might and Magic: Clash of Heroes the strategic level is about managing your pieces to launch attacks at your opponent while keeping enough pieces around to defend yourself. In Puzzle Quest, the match-3 mechanism is greatly enhanced by the character-building aspects taken from role-playing games. Henry Hatsworth in the Puzzling Adventure mixes match-3 and platformers, while 10000000 uses match-3 at the tactical level to power a dungeon crawler. Although combining genres this way can make for an excellent game, we wanted a simpler game . After all, Tetris is fun enough on its own!

To make the game more fun, we tried to expand the decisions the player had to make by allowing pushing from the sides in order to match. To avoid committing too much time pursuing these variants, we built paper prototypes. But even with more options, the game still felt too easy and uninteresting.

Feeling we had exhausted the search space, Merwan suggested we rotate pieces instead of pushing them. This was an intriguing twist, but it also meant that we would lose the “push pawns down a well” aspect of the push mechanism which so lovely tied into the theme. Still, it’s better to have a fun game that loosely fits the theme than the reverse, so we pursued it.

Turning it around

I went back to add rotation to the prototype. After two hours, I had rotation working, complete with animations. There was no matching; just rotation. But the rotation already felt fun. I spent quite a bit of time just toying with it, which is always a good sign:

One reason it’s fun is that you have many more options at your disposal: you can go anywhere in the grid and rotate four pieces right or left. It turns out that this is enough to re-arrange pieces in any shape (except for the fringe pieces). This observation led us to the idea of matching “runes”: patterns of colors. You would rotate pieces in order to build these patterns and satisfy the angry god.

Initially we envisioned large runes: letters-like shapes around 4x5 or even 6x6. We could have made the grid larger to accomodate that, but even before implementing the pattern matching we thought it would be more satisfying to chain smaller patterns rather than build towards larger ones. Large patterns require more moves, and felt more tedious to build.

Now, there only so many shapes you can make in a 2x3 grid, so we ended up with the familiar tetrominoes. At first, I tried to be original and had the green pattern be the following:

OO.

O.O

But it turns out that a disconnected pattern like this is harder to recognize on the board. It also made sense to have shapes with the same number of squares, in order to make sure they have the same probability being assembled on the grid. This also cut down on the possibilities. In the end, the game leans on the player’s familiarity with the tetrominoes, but you still have to get used to recognize situations that can make a pattern in one or two moves.

When I tried out the prototype, it had a great feel. Just at the tactical level, the player has interesting options. Do I go for the blue shape that’s a bit further, or do I try to assemble these four yellow squares lying around? Oh wait, now I’m seeing that this pattern of red squares is actually one move away from a match. It was fun just to look for near-match configurations. As you learn to recognize these configurations for all the patterns, you see potential matches everywhere.

Emergent gameplay

I’m always fascinated when the combination of simple mechanisms creates unanticipated and interesting gameplay opportunities. So when I discovered that our game had some, I was rather excited.

There is balance between the colors that naturally emerges from the rules. If you focus on matching the red shapes, you will have less red and more of the other three colours. Thus, you are forced to match other shapes, pulling you out of your comfort zone. This balance arises in other match-3 games as well, as long as all colors have equal spawning chances.

But playing with the prototype also revealed rich opportunities at the strategic layer. I categorized four of them: multi-matches, overlaps, combos and chains.

A multi-pattern match (or multi-match) is when one move matches two or more different patterns:

A multi-match can be tricky to setup, as you have to be careful of not matching the pattern prematurely while you move pieces around. Though messing up a multi-match can be comical, pulling one off is rewarding. It’s also fun to figure out the different ways to build them, and to learn the configurations leading to them.

An overlap is when one move matches two or more instances of the same pattern:

Overlaps are quite rewarding to build for the same reasons that make multi-matches fun. Overlaps are perhaps easier to setup due to requiring fewer pieces, and focusing on only one color.

Combos are pretty much a given, due to borrowing the random top row of pieces from match-3 games:

Though in the submitted game you don’t really have the time to arrange the grid in order to build elaborate combos, it’s still satisfying to pull a small one. Having a combo happen due to the random pieces falling is always nice as well. Had we had more time, we might have added a puzzle mode where you have to build the largest combo for a given board.

Finally, one of the more interesting ways to play the game is to aim for chains. A chain is a sequence of moves where every rotation you make is a match. Here is a 5-chain (starting with a multi-match and ending with a combo):

Unfortunately, in the final game we did not have time to signal these different trick moves to the player explicitly. Though combos, overlaps and multi-matches award you bonus points, and the god face reacts to combos, the connection is not obvious.

The timer forces you to play fast and safe, which tends to reward chains, but at the detriment of large overlaps and clever combo scaffolding. I would have liked to encourage the player to aim for these tricks more, as just matching the base patterns feels stale rather quickly. It’s a flaw that I would like to address in a remake, but I haven’t found the perfect solution so far.

The takeaway

We initially pursued a simpler ‘push’ mechanism that was a great fit for the theme, but ended up being too trivial to be fun. By looking at other games for inspiration, and by trying different ideas out, we iterated to find a core mechanism that, although not obviously tied to the them, at least felt good to play. From then on, we added visuals and animations to polish the game and better fit the theme.

The lesson here is: don’t be afraid to prototype a lot, and don’t be too attached to seemingly good ideas.

In the end, we aimed to build a fun take on match-3, and although the game could be improved to be more engaging, I think we succeeded.