Ludum Dare 39 Post-Mortem

So, Merwan and I made another game for Ludum Dare. It had been two years since our last entry, You Are The Münster (YATM henceforth), which we had a really great time making. Ever since, we have been meaning to get together for another round, but never managed to align our schedules until now.

You can play Bright Plateau right here. The rest of this post is a recollection of the 72 hours we spent making it, and contains minor spoilers (you should try the game first).

Day 0: Warming-up

In our timezone, the theme is announced at 3AM, in the night from Friday to Saturday. Merwan arrived Friday evening and, after we exchanged pleasantries, we spent a few hours throwing ideas at each other, talking about games we liked, why we liked them, what we thought they were lacking. I remember talking about simulations and tycoons, and how they can they can double as teaching tools for understanding complex systems. These genres would come up again later.

We went through the list of themes in the final voting round for this LD, which at the time was:

- Signal lost

- Parallel worlds

- Moving fortress

- Running out of power

- You are alone

- Start with nothing

- Machines

- Running out of space

- On / Off

- Connections

- Protect it

- You are not the main character

- 1 vs 100

- It spreads

- Different perspective

- 1 HP

We liked “Moving Fortress”, “Parallel Worlds”, “Running out of space”, “On / Off”, “Connections”; I remember discussing “You are not the main character” and concluding it was a dead-end, on the basis that any mechanism we could find would make the player-controlled character the main character in the eyes of the player. We felt pretty good about “Running out of space” winning, but we did not cast our votes, as we didn’t even have accounts to the new LD site at the time.

We then checked out a few of the top games from the last Ludum Dare for inspiration:

Out of these six games, we played: Honey Home, The Deep, Super Kaiju Dunk City and Snowed In. Little Lands looked awesome, but was Windows only, so we skipped it. For each game, we tried to understand its appeal, how they used the theme to good effect, and summarized what we liked/disliked.

I showed Merwan another LD game I had stumbled upon prior: Twin Condition. I really liked the clean aesthetic, the smooth animations, and the fact that you had to play both part of the levels differently, but at the same time:

I also showed him this prototype by rezoner, the author of Playground.js (among other nice things); I liked the effectiveness and look of the low-resolution 3D graphics:

This low-resolution is achieved simply by drawing to a small canvas (say, 320x180), then scaling it in the browser:

<canvas width="320" height="180" style="width: 960px; height: 540px;">

The browser will use a linear filter by default when drawing the scaled canvas,

which looks buttery (as above). You can use a nearest filter for maximum

crispness with the image-rendering CSS property.

Though unbeknownst to us, the visual presentation of Bright Plateau has been definitely influenced by these two games.

Then it was already 1AM. For our previous LD, we stayed up until the theme had been announced, started scribbling game ideas on paper, and went to bed only after we had nothing further to write down. This time though, we elected to start off with a good night’s sleep and to find out the theme in the morning.

Day 1: Finding the game idea

We woke up at around 9AM to discover the winning theme:

Running out of power

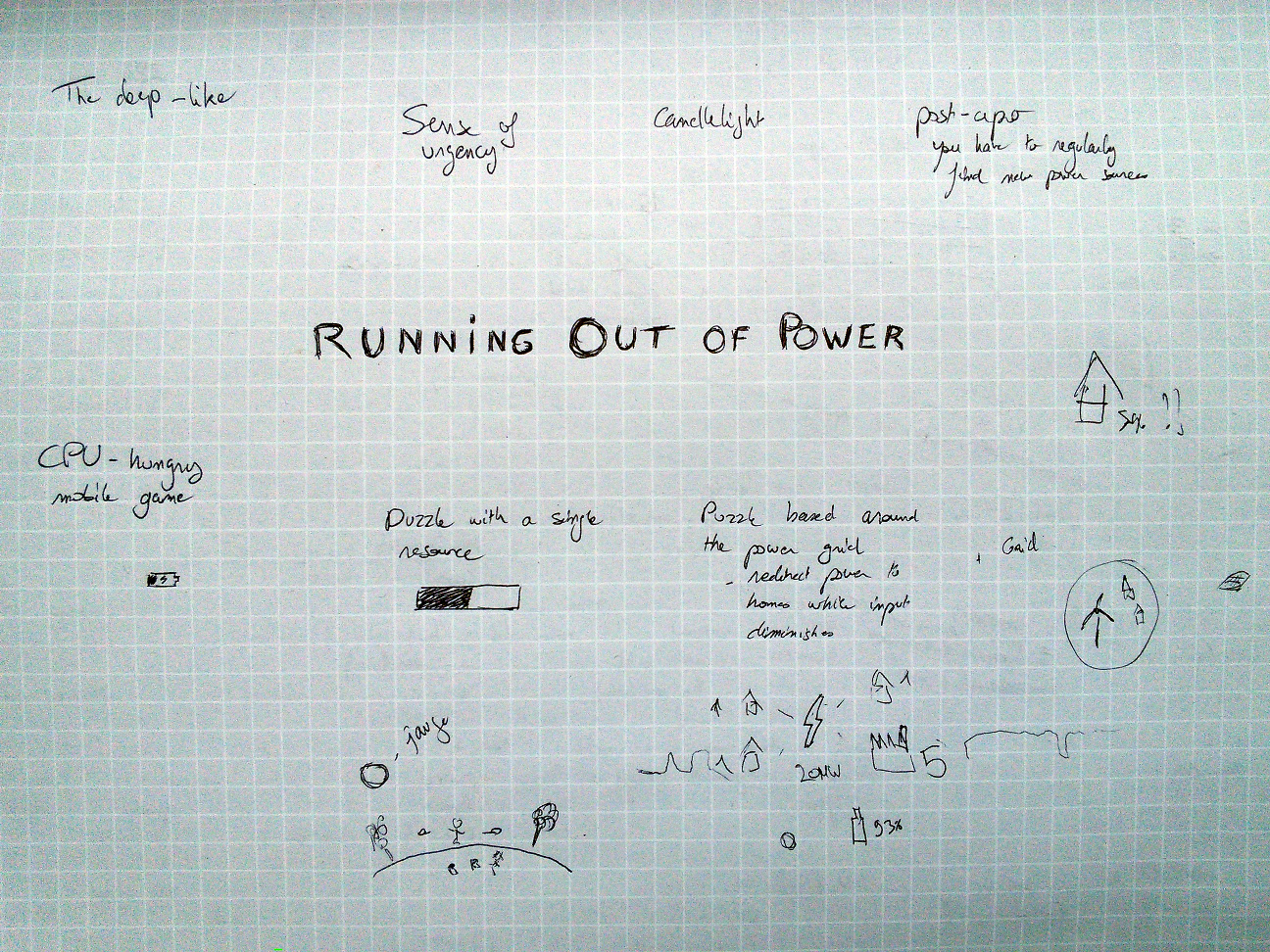

Well, we quickly skirted that one the night before, as it hadn’t inspired anything to us. But now the choice had been made. We started throwing ideas:

We quickly gravitated to the idea in lower right: “Puzzle based around the power grid”. Although at first the game was quite different than what we ended up with.

I remember pushing for a tycoon-like: there would be houses and plants to consume power, and you would buy and put power generators on the map to supply them. The power consumers would have different consumption profiles: plants would need a lot of power with low downtime, while houses would consume mostly in the day, but less at night. The consumption would not be fixed, but could vary from house to house. The generators would also produce a varying amount of power, depending on environmental conditions (wind for wind turbine, sunlight for solar panels), maintenance, efficiency… You earned money by providing power to consumers. Maybe this money would have been your score, maybe it would have allowed you to upgrade your generators. You can make out some of that on the doodles above.

With our previous game, we had learned that it was quite tempting to aim for a much larger game than we had the time budget (and ability) to build. In YATM, we had planned for a large world with four areas, each guarded by a boss that would be designed around the item kept in its area. In the end, we only had two areas, and zero boss.

This time around, we agreed to focus our design in order to have a game that would feel whole. Merwan suggested simpler rules; less simulation, more puzzle. What if instead of houses and plants, we had only houses? What if, instead of money, you would have a simple goal: power all the houses? What if, instead of a varying power distribution, we had only a binary state: on and off?

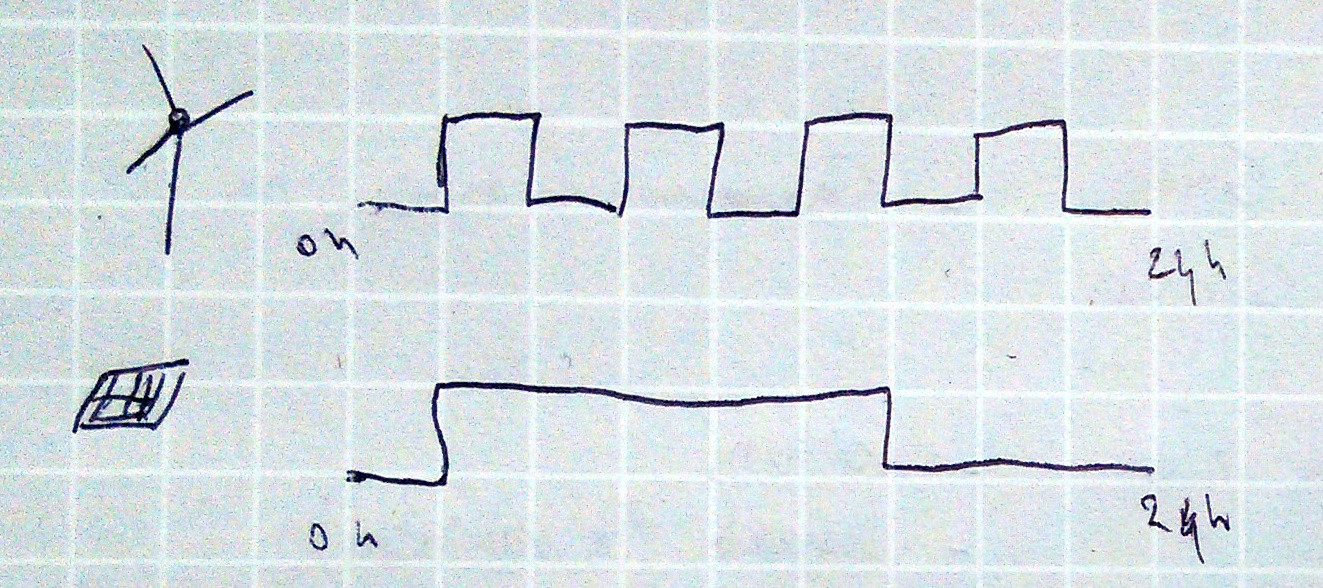

We thought about how that would work. You would put generators on the map to supply houses. Each generator would supply power to all the houses in an area around it, but it would also have a fixed distribution in time. So, for instance, the solar panel would power all the houses in a disc around it, but it would have a 50/50 distribution over 24 hours: 100% in daylight, 0% at night.

We tried to play with the idea in our heads. Would that be easy to understand? How would you play the game? How would you visualize the constraint of validating the power distribution over time? The time distribution was equivalent to a distribution in a third spatial dimension. So, instead of placing generators on a plane, you were really placing them in space. But how would that work, exactly? Placing objects in space on a 2D screen is not the easy to grasp, even when accustomed. Maybe display the time dimension below, like in Shenzhen I/O:

Merwan suggested to simplify, again. What if, instead of 24 slices of a day, we had only two: one slice for the day, one for the night. Then, we could show the grid in the day, have a little sun floating in the sky, and you would pick up the sun and drag to the right to see the grid at night. The coverage of the generators would change at night, and to solve the puzzle you would have to power all the houses at day and night simultaneously.

While I liked the idea of dragging the sun, I felt that going back and forth between the day and night would make playing unnecessarily frustrating, so I pushed for having them side-by-side. Merwan argued that it might be difficult to explain to players the sudden split between day and night. But then again, finding out that you could drag the sun away would not necessarily be more intuitive. And having the day and night portions side-by-side would probably be easiest to get right. We thought about potential ways to present this to the player, but did not find a satisfying solution, and elected to review this once we had the game running. In the end, we never reviewed it: the night levels are introduced without any explanation, but so far no player has complained about not understanding that they have to light all the houses on both sides to solve the level.

At this point, we felt this might be an interesting game: simple coverage alone would quickly be boring, but solving coverage with two slightly different sets of constraints? A tricky twist!

Prototyping on paper

We took this idea for a spin on paper before committing to code it.

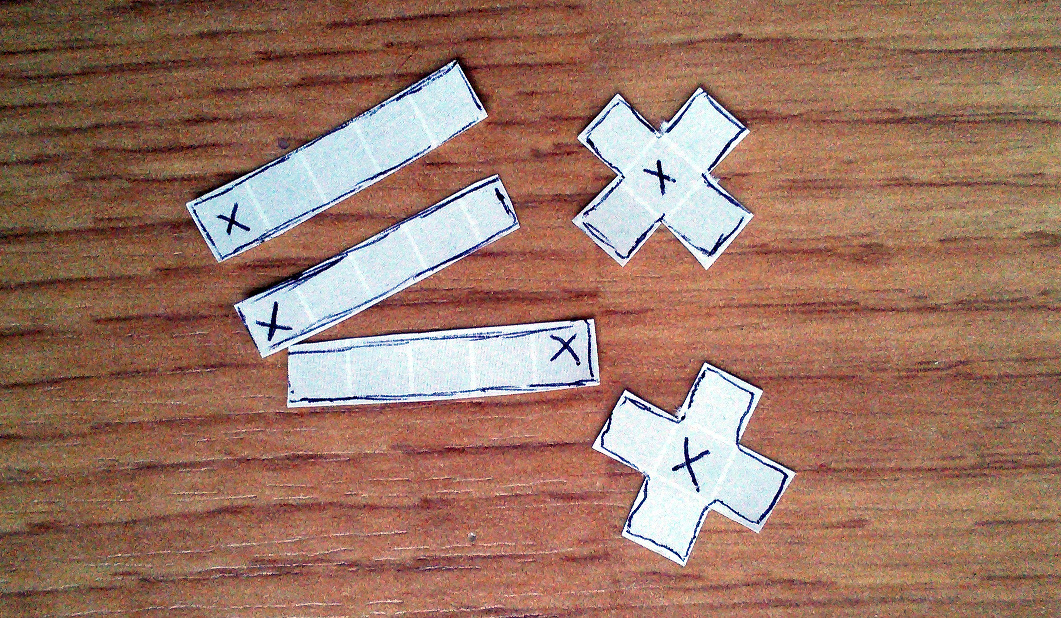

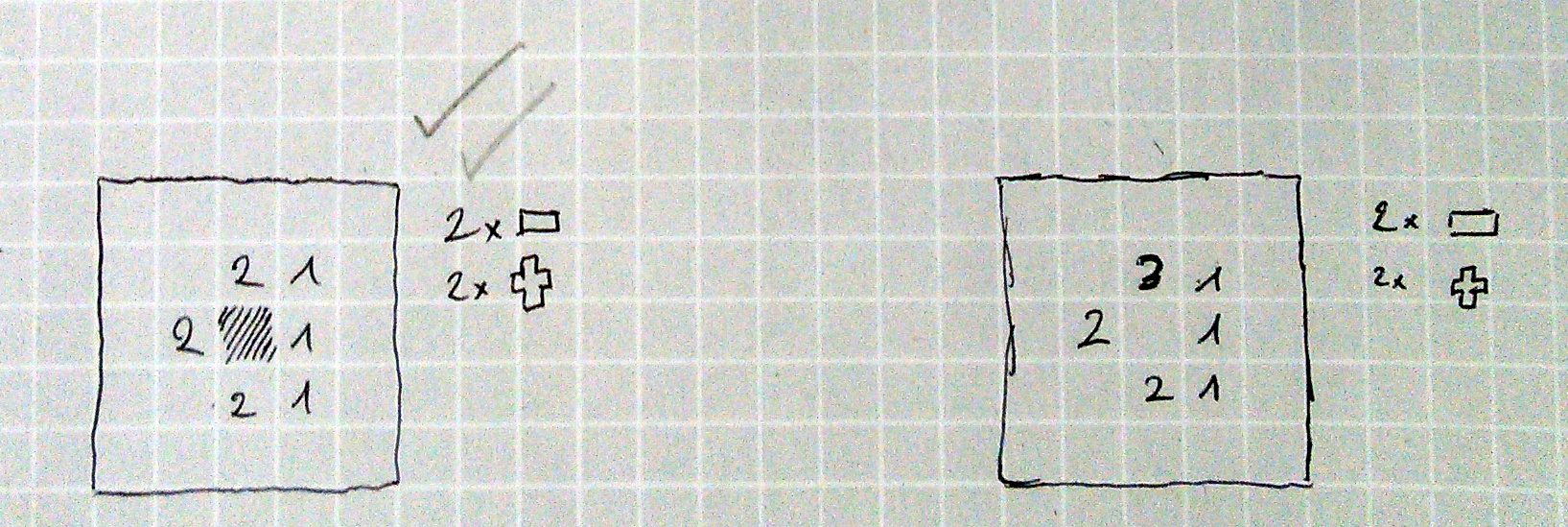

What should the coverage for the generators be? Again, we went for the simplest thing we could think of: the solar panel would power a straight line, and the wind turbine would power its immediate neighbors (in the final game, we did it the other way around, as it felt more natural while playing). I cut small lines and crosses out of paper, and drew a few levels to get started:

The number represent the amount of houses you have to power up. Each generator provides 1 unit of power to each tile it covers, so you have to overlap the coverage area of multiple generators to supply power to tiles with 2 or more houses.

In designing these levels, I went for the simplest non-trivial configurations of lines and crosses I could find, then simply numbered some of the tiles covered by the shapes. Numbering all the covered tiles would have given away the placement of the generators, and would have over-constrained the solution. Solving the levels would have been easy and boring. By not giving away too much information, you leave the player guessing. By not over-constraining, you also let the player solve the level in different ways, and that makes it more interesting. Although, you have to try to make sure there are no trivial solutions that you didn’t think of. Obstacles are a good way to prevent trivial solutions.

I handed these levels to Merwan, and he tried to solve them. He got one very quickly, and got stumped on another one. “Are you sure there is a solution?” he asked. “I think so” I replied, and I thought: this is challenging, he looks like he is having fun! Then I double-checked, and as it turned out, my level had no solution. When I fixed it, he solved it quite easily. I then made another one, this time making sure it had a solution, and one that was not too obvious. He solved it in around 1 minute.

We felt that the process of solving the levels was fun enough to go forward with this idea.

Solving the night conundrum

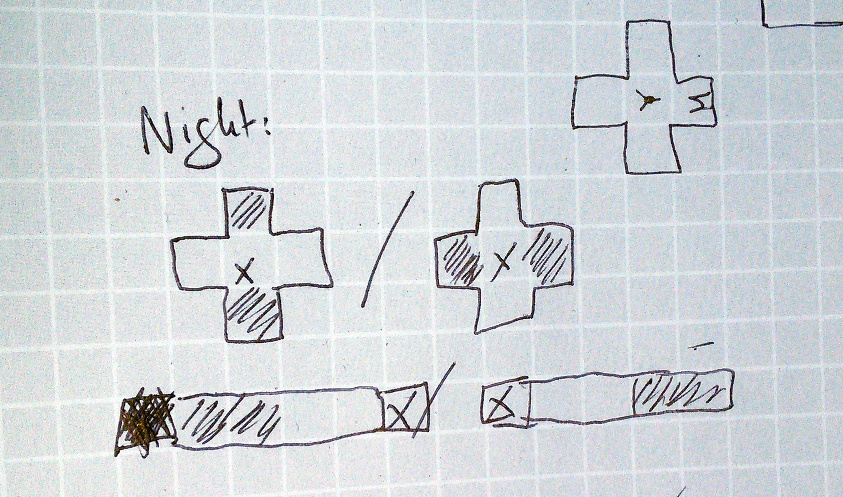

We really felt like we had to have the night in there, as it would make the game more unique. But how exactly would that work?

Maybe the houses you need to power would not be the same at night? Maybe, some houses would only need power during the day, and some would need power during the night? We felt that would make the puzzles hard to design. As we wanted to display the day and night side-by-side, your generators would necessarily be in the same place on the plateau in both sides, otherwise you wouldn’t be solving the same level, but really two separate levels. So, we went for simple again, and the houses you need to power would have to be the same on each side.

We wanted to have a real interplay between the day and night portions: you would have to go back and forth to satisfy the constraints on both sides. We needed to find a mechanism that would let you solve the day side, but you would have to refine your solution in order to solve the night side.

We started by reducing the coverage of wind turbines and solar panels by half. Now, we had to somehow overcome this power disparity between night and day. We thought about adding a third power generator that would work only at night. What would be its coverage area? We thought of a battery that would spread power to neighboring houses. Maybe we could charge the battery in the day, and depending on the amount of charge, it would power that many houses? If two generators are powering it in the day, it provides two units power at night. But how would we decide which houses would be powered by the battery at night? If the battery has one unit of power, but two neighboring houses, which one is powered? And more importantly, how to communicate that rule to the player? We didn’t know, so we changed it: what if the battery gives power to all the neighboring houses, regardless of its charge? That would be less annoying, as you wouldn’t have to care about the orientation of the battery. The battery would still need to be powered during the day, but receiving one unit of power would be enough. That made the day and night sides feel connected.

We did a quick check on the paper levels to see if the battery would still allow you to solve the levels we had. It wasn’t clear at this time whether the battery mechanism was interesting to play or not, but it was already 4PM, and we ought to start coding at some point.

Getting to a playable state

We both felt that an isometric view would be right for the game, and a very good pretext to play with THREE.js. We threw together a skeleton made of THREE.js and Playground.js (though we didn’t use much of the latter in the end) and got to work.

I took care of the game logic: first a grid you could put things on. Things are consumers, generators or obstacles. A consumer is just be a number: how many houses are on the tile. A generator has a coverage area, and we use that coverage in order to validate the level configuration: make sure every consumer gets as many units of power as it requires. Here is the first iteration of the level validation code:

let counters = new Map();

for (let th of this.things.keys())

if (th instanceof Consumer)

counters.set(th, 0);

for (let th of this.things.keys())

if (th instanceof Generator)

// Let the generator add to the power counters

th.distributePower(this, counters);

// Gather any mispowered (unpowered/overloaded) consumer,

// with the current value

let mispowered = [];

for (let [counter, power] of counters.entries())

if (counter.size !== power)

mispowered.push({counter, current_power: power});

// If there are no mispowered consumers, the level is solved!

let solved = mispowered.length === 0;I revisited it later to have separate counters for the night as well, and to handle the case of the battery distributing power at night only when powered in the day. But the principle remains the same.

For editing the levels, I simply represented them as strings in a JS file:

let LEVELS = [

{

generators: 'SS',

map: `....1.2...`,

},

{

generators: 'SSW',

map: `.....

.....

.221.

.2.1.

.....`,

},For YATM, we had used the Tiled editor, and while it had its downsides, it got the job done. However, using an external editor, there is an extra export step that gets in the way when you need to design levels quickly.

With the levels in a string, I just wrote a simple parser that emitted instances of the relevant objects according to the current character. It made editing levels trivial, as I just had to change a few characters in a text editor and reload the game to immediately see the result. This allowed me to iterate on the levels rather quickly on Day 3, when I put the bulk of the levels in the game.

By the end of Day 1, we could load a level, move and place generators, and the game could tell us whether the level was solved or not, and which tiles were lacking power. All of that in the console, not on the screen. Merwan was in charge of everything visual (he has the credentials for that), but we didn’t plug the view and the logic together until Day 2.

Day 2: Adding the visuals

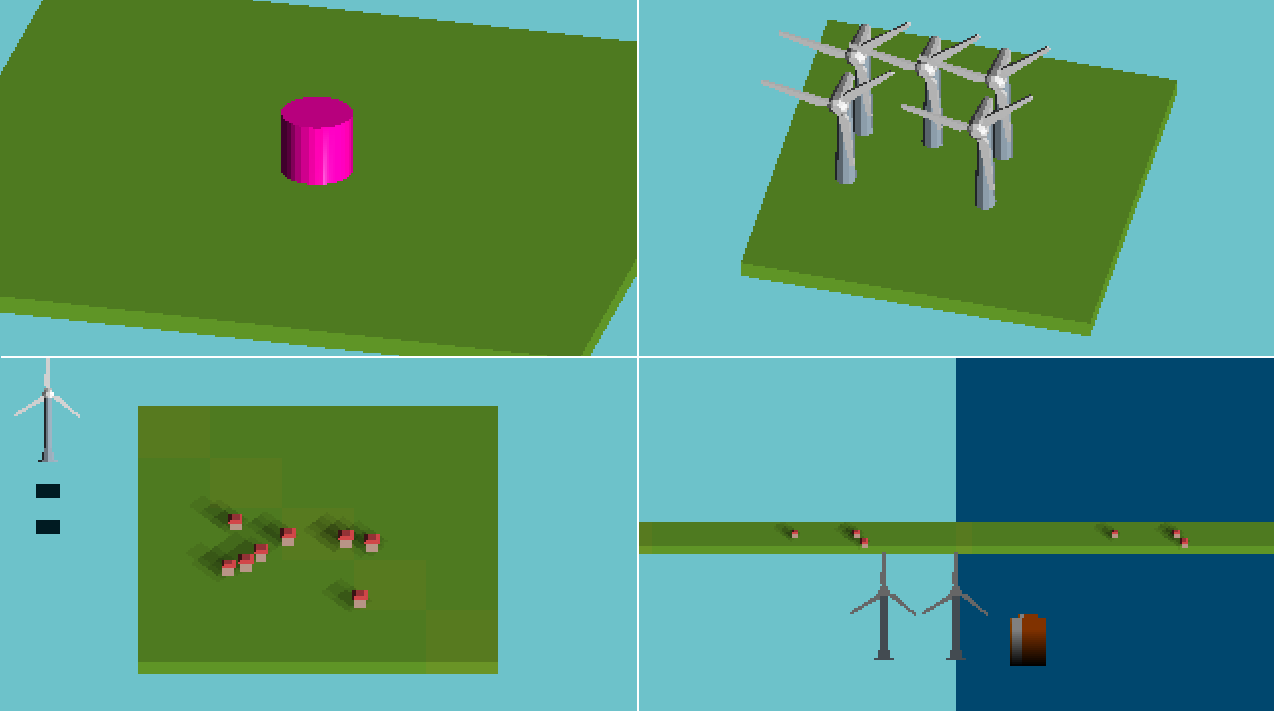

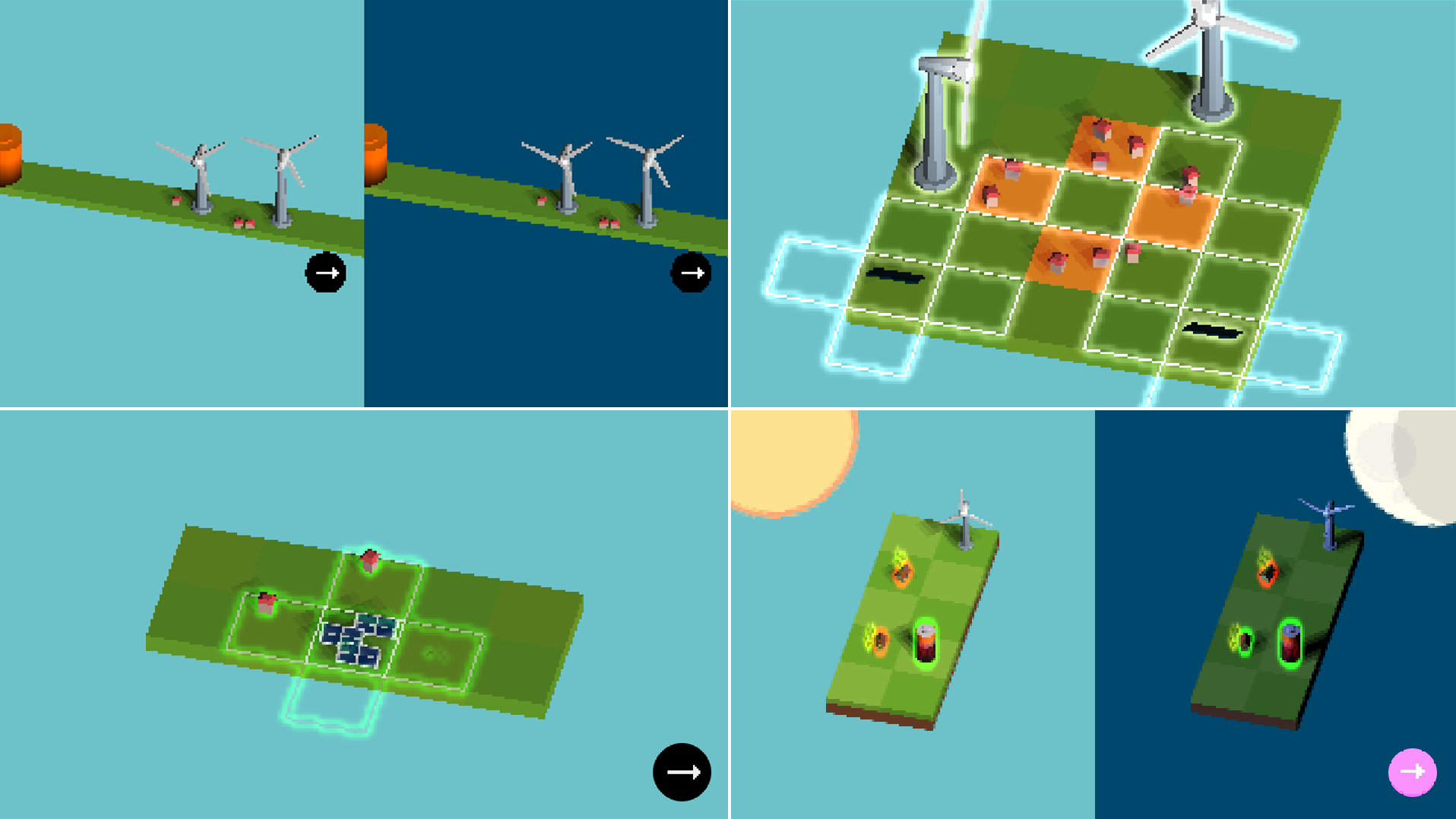

Here are a few screenshots of the visual progress for the first two days:

Why are wind turbines floating in the air in the bottom two screenshots, you

ask? This is the inventory that we cut from the game. If you look back to the

level data higher up, you will see a generators line. Initially, you were

supposed to pick the generators from the inventory area before placing them on

the plateau. The code was a bit tricky to get right, as we needed to have a

separate render pass just for the inventory, and specific picking code since the

inventory would live in a separate world space. Plus, we had extra logic that

dealt with taking things from the inventory and putting them back in it. But

then, it occurred to me that we didn’t need the inventory: we could place the

generators directly on the plateau, and the player would simply move them. It

made the code simpler, and the game more intuitive! I immediately told Merwan,

who agreed it was the right call—but only after initially hating me for cutting

the feature he had spent the last two hours working on.

The lower-right screenshot shows the side-by-side day and night views working. It was a bit simpler than anticipated to get working (THREE.js had example code for multiple views), but it was still tricky to get everything right. At first, we thought about duplicating the day scene into a night scene and keep the two scenes in sync with the model. Merwan suggested an alternative of rendering the same scene, but changing a few parameters on the fly. For instance, lights could be toggled on and off, or switched directions before rendering the night scene, and reset before rendering the day scene. This worked nicely.

The tricky part was rendering the coverage area of the generators, as they were actually different objects. The visual feedback for powered houses would also necessarily be different in both scene, as a house could be powered at day but not receive any power at night. We ended up rebuilding the coverage areas every time we set up the day or night scene, that is, at 120Hz. This is grossly inefficient and keeps the garbage collector quite busy, but as we only show the coverage for the generator currently under the cursor, it has not been an issue in practice. The feedback for powered house is less wasteful: it’s simply a list of objects that we give to an outline pass; we update this list before rendering the day and night scenes.

At the end of Day 2, we had something playable, although with only 5 levels, and the visual feedback was still rough. We parted ways as Merwan had to travel back home, and we kept hacking on the game remotely with regular updates over the phone, right until the deadline.

Day 3: night levels and polish

The last day was probably the longest as we stayed up right until the deadline to put everything we could in the game, and make a coherent whole.

Merwan worked hard on making sure the rules of the games were intelligible through the visuals. You can see in the collage above some iterations of the coverage areas and visual feedback for powered houses: from orange tiles signaling unpowered houses, to individual outlines around houses.

He also worked on visual polish: the dust particles when you plop a generator on the plateau, or making the day and night scene have a different feel, so it would be obvious to players that it was, in fact, the same plateau at different times of the day. The sun and the moon were a nice touch on that front, but then the shadow directions were all wrong, and we had issues with the moon coming in front of generators in the night scene. We would have loved keeping them, but due to lack of time, he cut them and opted for a starry background instead. He still took the time to put a YATM easter egg in the stars though!

I spent the day making the level validation work for the night levels, as we settled on the exact behavior of the battery. I then designed the night levels; we still had only one at that point. I aimed for 3 night levels, as I wasn’t really sure I could stretch the idea without making the levels feel repetitive. In the end, I managed to make quite a few levels more! I then spent around two hours making the sound effects in sfxr and the music in Sunvox. I was quite satisfied with the music, as the end result was about what I had in mind when I started. We also worked on buttons for navigating between the levels, and transitions.

When the game felt whole, I asked Marie to test it from start to finish. Having a fresh set of eyes on the game is crucial, as there are things that are obvious to the developers who have been working on it from the start, but may not be to players who might not devote more than a few minutes to the game. Her feedback helped me nail down the level difficulty progression, and gave us a roadmap of things to improve in the last hours of the jam.

Ten minutes before the deadline, I hit the “Submit” button on the LD page. We pat each other’s back over the phone on a job well done. We had made a game!

Aftermath

It’s a weird feeling, to know that three days earlier you had no clue of what your game would look like, or if you would even be able to get something fun working this time around. But, now, we have a game we can show to friends and colleagues. The feedback on the LD page has also been overwhelmingly positive. It’s a great feeling!

I would without a doubt recommend to anyone who has ever wanted to make a game, to participate in a game jam. I feel it is a good way to learn how to focus your game design and coding efforts in order to make something playable and complete. It forces you to relentlessly cut, cut and cut, until you have a core that is both fun enough and realizable. This is quite different from the greenfield development of side projects.

And even if you don’t finish or submit your game, the experience itself is something that is worth going through, as it will create memories that you will gladly reminisce later down the road. I know I will.